Submerged Literature Rises Anew

In summer 2002, Vitalis Publishers and its bookshop were devastated by the worst flooding in centuries. For weeks, we were cut off from the outside world, without power and with the telephone lines down, making it impossible to continue with the business of publishing. It was not until the floodwaters receded that the extent of the damage – running into millions – was revealed. This was the hardest test in the company’s ten years of existence at that time. Despite the destruction, provisional publishing operations were able to begin anew by autumn 2002. The first catalogue after the flood adopted this motto from Hölderlin: “And flood and rock and the power of fire Man vanquishes by art”, and it was in this spirit that rebuilding began. While still under the influence of the catastrophe, our publisher Harald Salfellner compiled a report on those August days when the waters rose.

Bohemia in the Sea

It’s been raining in Bohemia for days on end. The water levels are rising, and Prague is taking arms against a sea of troubles: A flood now seems imminent. As the floodwaters reach the Czech capital on August 12th, Český Krumlov and other towns on the upper reaches of the Vltava are already submerged. The dams are barely holding.

Throughout the afternoon, the broad and bloated river rolls ominously under the Mánes Bridge. Tree branches and household goods sweep past us, bobbing up from under the foam before vanishing once again into the murky depths. The water is still a few meters below the banks, but the rain continues pouring down incessantly on the river’s seething surface. Though the weather’s as cold and clammy as in November, the streets and squares are filled with people. They stand on the bridge and gaze at the water, before moving on past the Klárov Park towards the Charles Bridge. We decide to join them, but for us it’s a race against time. Behind the old Customs House, the brown water is already lapping at the entrance to the narrow street – and there’s nothing here that could hold it back. The radio reports that engineers in the south have had to open several floodgates in order to prevent the retaining dams from bursting. The task now is to prepare for the consequences: An enormous flood wave, overshadowing even the high-water record of 1890, is heading inexorably towards Prague. Rumours appear from nowhere, spread quickly, and then disappear. Everyone’s guessing, nobody really knows. The water level will rise by two meters! – No, three! On the island of Kampa, the water will mount to the rooftops... It’s not true! Barriers have been erected; the city is ready for anything!

At last, the sand arrives; big Tatra lorries deposit their loads on the cobblestoned streets, where white plastic sacks are piled up ready for use. Sirens wail; the city seems packed with ambulances making their cacophonous way through the crammed streets and squares. Thousands of people are forced to leave their apartments; evacuation is now well under way. For the past few hours, any cars parked in the affected areas have been towed away. Now, the army is moving in – hordes of young men from the Prague barracks. Police officers are patrolling the disaster area, trying to bring order to chaos. Everywhere, the mood is still hopeful, still positive; yet in the city’s narrow streets, bustle and confusion rule. People are visibly worried. Together with shopkeepers, waiters and civil servants, the local inhabitants are labouring with the soldiers to construct a dam out of sandbags. Women fill the sacks, and men heave them into the designated positions, or else they drag their heavy load to the surrounding doors, windows and ventilation shafts. No-one has any experience at this, none of these people are experts at what they’re doing, and nobody appears to be in charge. It’s been generations since Prague last experienced such an inundation. Many of these willing helpers could work more effectively under proper leadership, yet their energy is dissipating almost without results. Not even the soldiers really know what has to be done. It looks as though they’ve been deposited here without commanding officers, without adequate equipment and without any clearly defined task, simply so that they can help out here and there as they see fit.

In the shops and stores, goods are being stacked up on the upper floors, for it’s no longer possible to move them out of the danger zone: The access roads have been blocked off. The night passes in hectic activity; but the early morning hours of August 13 are filled with an eerie silence. No-one is allowed to enter the street, all the local people have left the area – some of them against their will – and the authorities have declared Malá Strana a disaster area. The island of Kampa, just a few hundred meters away, is already deeply submerged. Yet our forecourt is still dry, and so we dare to raise our hopes once again – although the water levels, too, have risen sharply overnight.

The sandbag barriers are weak; after only a few hours, the sand is already wet through. Minutes and hours pass with painfully slowness, and still the Vltava hasn’t reached its highest point. At short intervals, we walk down to the Klárov. On TV, there’s practically no specific information, although ČT 1 is reporting around the clock – and they’re certainly not telling us whether the sandbags in front of our bookshop will hold up against the pressure... We’re hoping, doubting, worrying and praying; and we’re watching from a distance as our fears are confirmed and our hopes go under. The barrier succumbs, in a dismally unspectacular fashion. No raging torrent, no tumbling, streaming, foaming flood, no crash and rush, no swirling, whirling, surging waves: just a slow, inexorable trickle of murky water into the quiet street, over the footpaths and front gardens, through the gaps and cracks, into the shops and houses, through the breaking windows, into every available nook and cranny. Soon, the water reaches the Metro station, pouring sluggishly but relentlessly down the stairs and escalators, and filling large sections of the tunnel system. After less than an hour, our bookshop’s forecourt is flooded. This calamity makes for a weirdly peaceful scene; we stand and stare, with our hearts pounding.

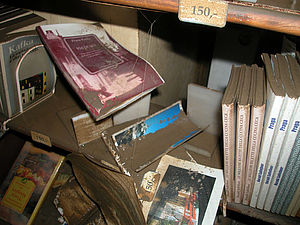

Malá Strana, the idyllic “Little Side” of the Vltava River, is very badly hit by the flood; and it’s here that the Vitalis publishing house is located. Within minutes, the only German bookstore in Prague has fallen victim to the slimy deluge. The entire stock of books and all the furniture and fittings have been ruined, but only later will the full and terrible extent of the damage become apparent. The progress of this catastrophe was so slow, so measured... so stately, almost. At the moment, though, not much damage can be seen; it almost seems we might yet have time to come to terms with our nemesis. The company signboard is still hanging, though it’s half-submerged in the meters-deep water.

And now there’s clearly no hope at all – not even for the most expensive volumes, which we had hastily carried upstairs. Our premises are filled to the topmost ceiling with floodwater. The Vitalis Bookshop in Malá Strana no longer exists. In a matter of hours, a literary meeting-place for natives and visitors has become a thing of the past, sunk in the flood; not a trace of it remains. And after the water’s influx, things get even worse. Anyone familiar with the most basic laws of physics knows there’s simply no prospect of a merciful escape; and the neighbouring storerooms – installed in the former premises of the publishing house – have also been ravaged by the flood. We begin to realize that tens of thousands of books are now stewing in a stinking, slimy soup, and that a decade’s efforts to build up the company have been erased in a single day. Yet we still don’t want to give up hope of a miracle until we’ve seen the evidence with our own eyes. Later, we’ll break into the storerooms with wrenches and crowbars – and only when the door swings open to reveal the spectacle will we truly grasp the fact that everything has been ruined.

Meanwhile, there’s still no respite from our worries and hopes. If the water rises any further, it will also reach the premises of our publishing business. And indeed, a short time later, the unthinkable actually happens: The water climbs ever higher before streaming across a meadow and pouring down into U Železné lávky, a street located at a lower level in our part of town. On this spot, around a century ago, there used to be an iron footbridge to the Old Town, across the then-untamed Vltava. A safe path over perilous waters – this, we had felt, would be a fitting location for a publishing enterprise conceived as a bridge between cultures.

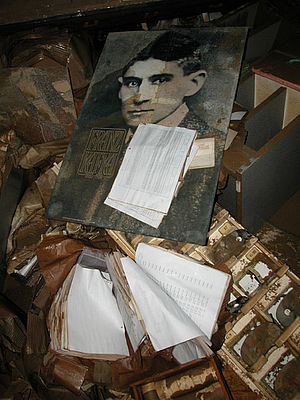

At Klárov Square, the weeping willows are now protruding from the muddy pond that’s formed here. Swans and ducks are busily disporting themselves, clearly delighted at the sudden enlargement of their habitat. On the other side of the pond, a Franz Kafka poster stands out on the wall of the building that hosts our publishing enterprise: The great writer is up to his chin in water. The water birds seem attracted to Kafka’s melancholy eyes, for they keep paddling to and from across the narrow street before him.

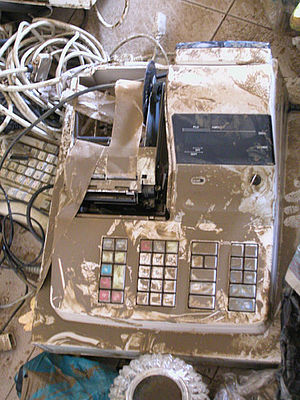

Here, too, the flood knows no mercy. It forces its way into the studio facilities on the lower level, fills the rooms to the ceiling and lays waste to everything: furniture, telephones, electronic devices, computers, archived documents and files. Later, two workers from the Carpathian Ukraine will help us to liquidate our assets; and as they witness the devastation, their expressions of sympathy will carry echoes of their own experience: Strašné! Hlavně zdraví! Terrible – but at least you have your health!

Faced with such losses, one calculates the work done, the energy invested, the sheer stubborn persistence over the years; one thinks back on all the effort expended under sometimes difficult circumstances; and one simply cannot believe that it’s all been in vain, that all – apparently – is lost.

The “rainy season” is followed by hot, humid, late-summer days. The heat makes it harder to clear out the tons of swollen, fermenting books from the dark and gloomy storerooms. With no electricity available, there had been no possibility of using mechanical assistance – and, in any case, access to the disaster area was still restricted, to discourage looters from plying their trade. Only after endless explaining, pleading and begging was anyone ever permitted to cross the “border”.

When I opened the bedroom windows on those muggy summer nights, I was met by the sickening stink of rotting paper. For days on end, this repulsive smell clung to my fingers and refused to be washed away. But though the air was heavy with the whiff of putrefying paper, the evidence of our eyes was even more oppressive; for what we saw were the corpses of dead books, damp, mouldering, sticky and slimy, piled up in heaps and waiting for the bulldozer – then crammed into containers, grotesquely twisted, awaiting their final removal. On this dismal spot, we all felt the conviction that books are something more than mere items to be bought and sold. Even in the depths of the container, they retained a certain glamour; and often, in those days, we would point at a tattered cover, a mutilated book, as if to say: There goes Leppin’s novel, on its last journey into the dark.

At long last, it’s all over and done with. No longer will we clamber over the heaps; never again will we struggle with clumsy tools to break down the sludge-bespattered doors; finally, we’ve pushed our very last loaded wheelbarrow from the dimly-lit vaults. A Czech couple, clearly appalled, take a peek into the container and whisper: Bože, to je škoda. One might render this into English as: Good God, so much damage! Yet their faces make it clear what they’re really trying to say: My God, what a pity...

For the sake of these two people, it’s worth going home, brewing up some coffee – and starting afresh.